Fundación Alpe has been a stronghold for skeletal dysplasias throughout the years, with a clear vision of what is needed today to improve the lives of people with skeletal dysplasias but also with an understanding that, as science evolves, what is considered standard now may become obsolete in the future. I believe that vision explains why they set Alpe y un nuevo horizonte (Alpe and a new horizon) as the signature for this edition of the congress.

As a member of Alpe's Scientific Advisory Board, I was asked to talk about the changing scenery in the healthcare for achondroplasia and skeletal dysplasias. I am grateful to the strong leaders of Fundación Alpe, Carmen Alonso Alvarez and Susana Noval Iruretagoyena for the opportunity to talk about the current status of pharmacological therapies for achondroplasia and future perspectives during the congress.

Here I share my presentation with our 17 readers, hoping that the topics discussed there (and here) will help families interested in therapies for skeletal dysplasias to stay updated about the developments we are seeing in the field.

So, where do we go from here?

Achondroplasia has been known for thousand of years. Archeological treasures have been found in all continents depicting the typical features of this skeletal dysplasias (Slide 1).

Slide 1. Achondroplasia has been depicted by many ancient cultures all over the world.

A long journey

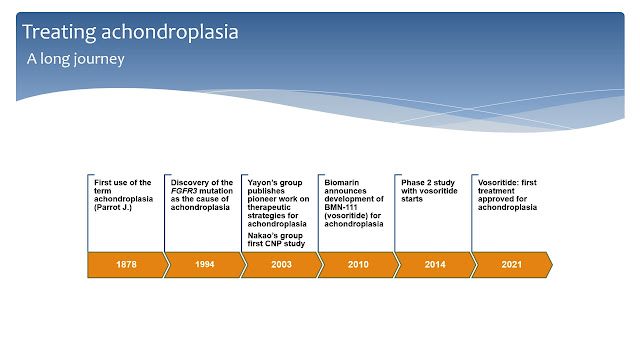

The term achondroplasia was used for the first time in 1878 by the French doctor Jean Parrot to describe a condition where there was no cartilage growth (Slide 2).

It took more than a hundred years from that first paper for science to identify the gene mutation that causes achondroplasia. A recurrent, single point mutation in the gene which encodes the enzyme Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 (FGFR3) was finally linked to achondroplasia in 1994. After that, scientists quickly learned that the recurrent G380R mutation in FGFR3 makes this receptor enzyme excessively active leading to bone growth arrest.

Meanwhile, a few pioneers started to study the mutation and almost ten years later the first attempts to find therapies were published. In 2003, Dr. Yayon group designed the first antibody against FGFR3 while the Japanese group leaded by Dr. Nakao released the first study with C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) in the cartilage growth plate. CNP was discovered to antagonize the activity of FGFR3 in the growth plate and this lead to further discoveries.

In 2010, Biomarin introduced a first CNP analog, BMN-111, in their pipeline. In 2014 they started the first study of BMN-111 (now known as vosoritide) in children with achondroplasia. Finally, in 2021, after a long clinical development journey, vosoritide was approved by major regulatory agencies and is already being used in several countries for the treatment of achondroplasia.

Slide 2. A timeline of achondroplasia.

One aspect of the scientific research about achondroplasia is that the interest about this skeletal dysplasia got a booster after the announcement of the phase 2 study of vosoritide (Slide 3). Someone reviewing the scientific activity about achondroplasia might reach the conclusion that the increased interest was mostly driven by drug developers introducing new potential therapies. This is only partially true. In fact, although it has been recognized that achondroplasia is the most common form of skeletal dysplasia, and that a relatively fair knowledge about its typical clinical features were already in place in 2004, many questions regarding clinical and developmental aspects were still poorly addressed. In the last few years many publications have focused on epidemiological, clinical and developmental aspects of achondroplasia rather than simply working with potential therapies (Slides 4 and 5).

One aspect of the scientific research about achondroplasia is that the interest about this skeletal dysplasia got a booster after the announcement of the phase 2 study of vosoritide (Slide 3). Someone reviewing the scientific activity about achondroplasia might reach the conclusion that the increased interest was mostly driven by drug developers introducing new potential therapies. This is only partially true. In fact, although it has been recognized that achondroplasia is the most common form of skeletal dysplasia, and that a relatively fair knowledge about its typical clinical features were already in place in 2004, many questions regarding clinical and developmental aspects were still poorly addressed. In the last few years many publications have focused on epidemiological, clinical and developmental aspects of achondroplasia rather than simply working with potential therapies (Slides 4 and 5). Slide 3. The number of publications about achondroplasia has been rising in the last ten years.

Slide 4. Research on drug therapies for achondroplasia leads to improvement in healthcare.

Slide 5. The first International Consensus for the management of achondroplasia.

Real people. Real problems.

Why are these new guidelines and a first international consensus on healthcare for achondroplasia so important?

In the real life, daily medical and social challenges are common place both for children and adults with achondroplasia (Slide 6 just provides a few examples extracted from social media). These new publications aim to address the key medical elements that may improve health and quality of life spanning all age groups. It is clear that we need to do better.

Slide 6. Real people. Real problems.

Progress

While learning and understanding the natural history of achondroplasia will certainly lead to better healthcare, it is undeniable that the research towards solutions to control the overactive FGFR3 are in full speed right now, with many potential therapies in various degrees of development (Slide 7).

Slide 7. Current and potential therapies for achondroplasia.

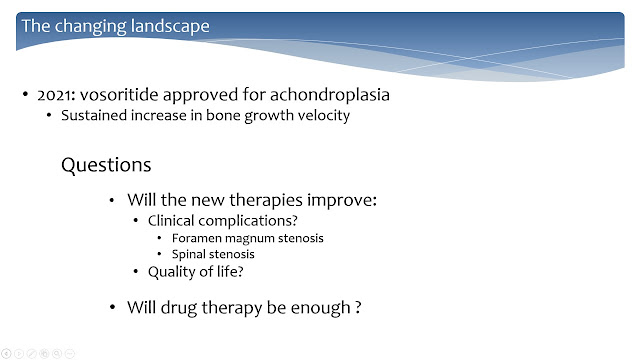

As we know, last year vosoritide was approved for the treatment of achondroplasia based on its positive effects on bone growth velocity and incremental and sustained growth over two years (Slide 8). There was some controversy about choosing growth velocity as a parameter of efficacy without observing other clinical aspects that are relevant in achondroplasia. However, having in mind that bone growth is a slow process, using changes in growth velocity seems to be a reasonable way to verify efficacy in relatively short term. The known clinical complications seen in achondroplasia are frequently related to restricted bone growth. It is possible that over years (so long term) we may see that these complications will become less prevalent, but this will take some time more to be confirmed.

Furthermore, if together with improvement in standing height, we expect that there will be a reduction in the frequency of medical issues in children receiving pharmacological therapy, then another aspect that should also improve is quality-of-life (as measured through several tools), which is known to be lower in achondroplasia compared to the general population.

Another important question that needs to be addressed has to do with an understandable but unrealistic expectation many parents may have today about the results of any pharmacological therapy (Slide 8). Having their child under drug treatment should not preclude the need for continuous specialized follow up, at least for the next few years, until we get more evidence that the treatment may really reduce the incidence of orthopedic and neurological complications. Let's say we need to wait and see whether the treatment could bring the child to a level of healthcare need that is typical of the average child. So, as for now, just pharmacological treatment is not enough.

Slide 8. The changing landscape.

So, where are we now and where do we go from here? (Slide 9)

As countries approve and include vosoritide within their pharmacopeias, there have been many questions raised on social media related to access to treatment. Vosoritide is a high cost medicine, at a level that is not affordable for the vast majority of families interested in offering this option to their children. The developer and payers must find a common ground where the reward for being the pioneer in the field is well paid off while access is amplified.

However, access is only one the challenges ahead. The social media is indeed a source of helpful information (at least related to our topic here). An issue that has been raised by families looking for treatment for their kids is the little, if any, knowledge professionals that assist kids with achondroplasia have been demonstrating about the new pharmacological therapy and healthcare management in general. Since experts in skeletal dysplasias usually work in specialized referral centers, effort needs to be done to spread more effectively the knowledge not only about pharmacological therapies but also on the management of achondroplasia in the primary or secondary care settings. This, in turn, may also help improving access to therapies. Statement papers and the Consensus depicted in slides 4 and 5 may be a good starting point to extend the knowledge gained in recent years to the front-line of healthcare.

Slide 9. The future of healthcare for skeletal dysplasias.

A new horizon

Finally, as Alpe has envisioned in the recent conference, a new horizon is ahead. With all the research performed to understand the FGFR3 mutation in achondroplasia, how it works and affects bone growth, much has been learned about the overall bone growth and development process.

The FGFR3 pathway is a powerful growth brake in the cartilage growth plate. It is a very important modulator of bone growth working to balance the activity of several other agents that promote bone growth. If it is working less than normal bones grow excessively and may cause medical issues; the same occurs when it is working too much as we see in achondroplasia.

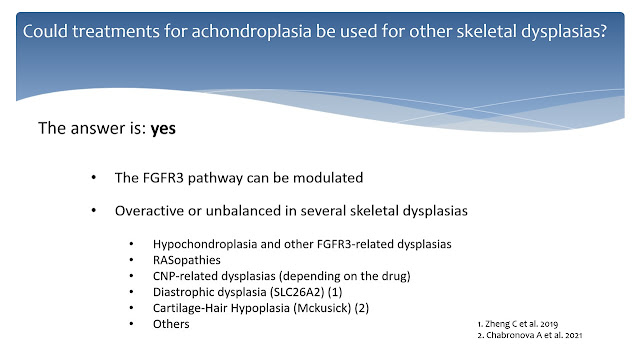

We now know that FGFR3 activity can be controlled. The question is whether this knowledge can be used to see if controlling FGFR3 activity would be helpful for other skeletal dysplasias. The answer to this question is yes (Slide 10).

It would be common sense to deduct that other skeletal dysplasias where in some way the FGFR3 pathway is unbalanced could be managed by vosoritide or other drugs in test for achondroplasia. For instance, other FGFR3-related dysplasias such as hypochondroplasia or other very rare cases where FGFR3 mutations cause proportionate short stature.

Another example would be the CNP-related dysplasias. In these cases, most of the time the mutation causing the dysplasia is located in the CNP receptor, so giving CNP analogs would not likely help improving bone growth, but agents targeting FGFR3 directly, such as infigratinib, could be helpful.

Another example shown in Slide 10 are the RASopathies, such as Noonan syndrome, where the same enzymes (the MAPK pathway) activated by FGFR3 are overactive due to mutations in regulatory proteins. In this case inhibiting FGFR3 could help reducing MAPK activity to improve bone growth.

Other skeletal dysplasias might benefit of the use of anti-FGFR3 agents and there is already evidence in the literature, for instance in diastrophic dysplasia and in Mckusick syndrome, that FGFR3 might be overactive and contributing to impaired bone growth.

It is also foreseeable that treatments developed for achondroplasia might benefit children born with other bone growth impairment conditions. It is time to multiply the efforts to evaluate these new potential therapies for other skeletal dysplasias.

Slide 10. Treating other skeletal dysplasias

The future is around the corner

Skeletal dysplasias are disorders which affect the body in development. These pharmacological therapies may, in the near future, help children to grow better, bringing together many benefits that go beyond achieving a higher final stature. One of them, which I have already referred to in the past, is very simple. Let's just imagine a time where a child with achondroplasia will be living the same ups and downs any average child lives as they grow into adulthood. No more, no less. I think this is a good perspective to have.

No comments:

Post a Comment